A brief overview of UCD student unrest and radicalism from 1968-70

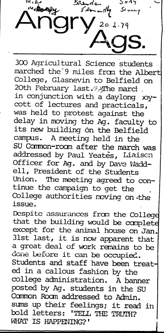

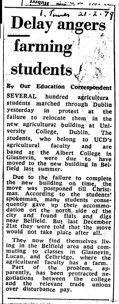

UCD purchased Belfield House in December 1933 [1]and between 1948-58 acquired a number of adjoining properties with the intention of creating a new campus to relieve the chronically overcrowded Earlsfort Terrace. UCD’s student population had expanded from little over 2,000 in 1939 to over 10,000 in 1969.[2] Most of these were housed in the half-completed Earlsfort Terrace building, which, even had it been finished, was intended for only 1,000 students.[3]

As early as 1963, concerns were raised over the planning of the move to Belfield. The Irish Times wrote that “the prospect of finding lodging for students (was) causing more and more concern …The area is not one in which students will easily find places to stay, since most of the houses there are designed as family homes’’. [4] However, building went ahead and in 1964 Science became the first Faculty to relocate to Belfield. The Irish Times described their new facilities as “severely functional” with “clean planning, spaciousness and a clever use of colour…relieving the eye of monotony”. [5]

In January 1965, U.C.D. President Dr. Jeremiah Hogan speaking at the conferring of degrees admitted that “the transfer of Arts would be the central and most complex operation”.[6]of the relocation.

According to the Irish Times’ UCD Correspondent the new restaurant in the Science building in Belfield was proving “insufficient to meet demands’’.[7] When food prices then rose by 20%, students threatened a sit-in but this was called off at the last minute.

A year later it was discovered that the new Belfield Arts block would “be too small to cope adequately with the projected number of students availing of it in the early 1970s’’.[8] In February 1968, the Minister for Education Donogh O’Malley met representatives of the U.C.D. Students’ Representative Council (SRC) who were anxious that the students’ building in Belfield be completed before the proposed Arts faculty move in 1969. [9]

Meanwhile, conditions in Earlsfort Terrace were worsening and there were murmurs of unrest. In June 1968, medical students held a sit-in in the Medical Library demanding that it be kept open over the summer months. Students calling for longer opening hours also occupied the Arts Library.

Not to be outdone, Science students in Belfield threatened direct action unless improved library hours were negotiated. In October of that year, Third Year Chemistry students boycotted lectures and “rearranged their seating-plan in lecture theatres to frustrate roll call”. This protest was against what one student described as the ”fact that out here in Belfield the methods are more suited to a primary school than to a university”.[10]

In Belfield, the Arts building was finally finished in October 1968 after a 15 month project costing £IR 1.6 million.[11]

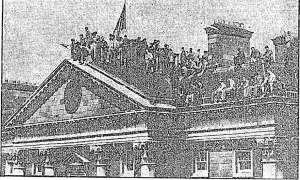

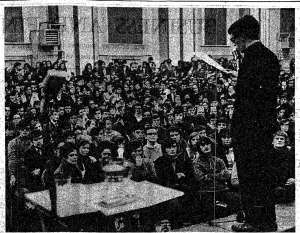

On the 8th of November 1968, more than 2,500 thousand students occupied The Great Hall in Earslfort Terrace for over two hours in protest against the college authorities’ refusal to allow a ‘teach-in’.[12] [13]

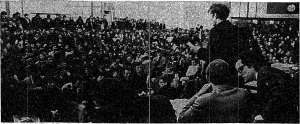

Student Meeting (November 1968, Great Hall, Earlsfort Terrace)

On Friday 29th November over 120 architecture students held a sit-in for a day and a half to “draw attention … (to) a fall in standards”. at the college[14] Just over a week later, 5,000 students marched to the Dail over the issue of grants.

In December, a recently formed group, Students for Democratic Action (SDA) held a 400 hundred strong ‘sit-down’ protest outside a meeting of the Academic Council.[15] They were protesting against the Council’s refusal to recognise the Republican Club as a society. The council postponed the meeting with some members managing to leave by the door, others by the window. The SDA then promptly decided that the Academic Council did not merit the authority to recognise the Republican Club. They followed this by declaring their group the real and legitimate Academic Council, voting overwhelming to recognise the Republicans.

In January 1969, the SRC issued a manifesto criticising what is described as the apparent lack of planning and consultation on library facilities at Belfield.

In early February 1969, it was announced in The Irish Times that Belfield would “not posses a library block (until) October 1970’’. Further still, the student’s union building would not be constructed until 1971.[16]

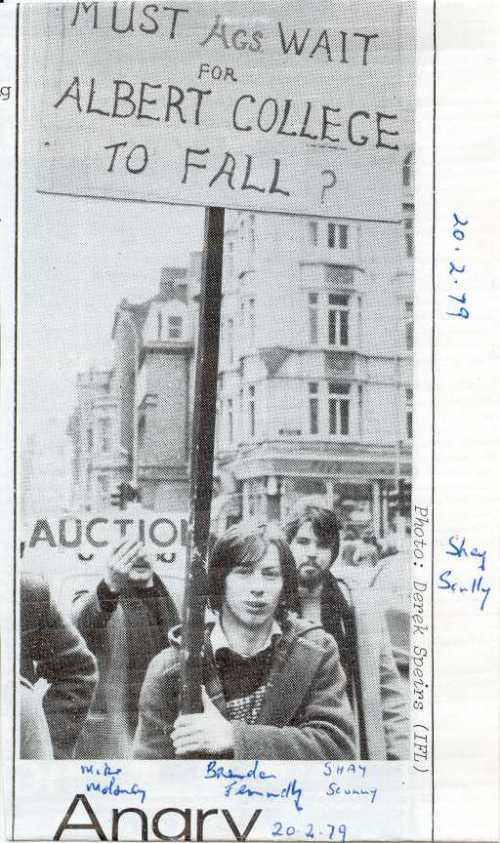

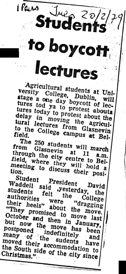

On Wednesday, 26th of February 1969, the SDA organised a mass meeting. It was resolved that there would be no move to Belfield until (i) full library services were available; (ii) that the Governing Body should be abolished; (iii) that a 50-50 staff / student committee should be set up to govern the college; (iv) and that students should occupy the administration building as soon as the meeting ended.

Just after lunchtime, over 140 students occupied three rooms of the administrative wing of the college’s building at Earlsfort Terrace. They barricaded the doors and remained overnight.

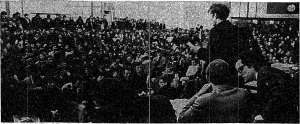

Student Meeting (February 1969, Great Hall, Earlsfort Terrace)

The students were protesting against what The Irish Times described as the “the proposed move of the university to Belfield…which they claim has been poorly planned and may require students to work under inadequate circumstances”.[17] The occupiers used a loud speaker system to address fellow students and distributed leaflets from the ”liberated zone of UCD’‘ printed on the ”college duplicating service” which was in one of the occupied rooms.[18] The Irish Independent proclaimed that the “black flag of anarchy (now flies) over U.C.D.”.[19]

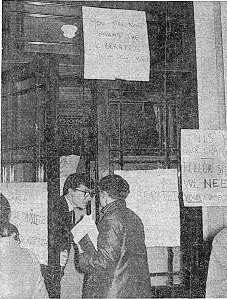

Occupation: Sign on door reads 'You are now entering the liberated zone of UCD'

The occupation ended at 11pm the next day. The decision was taken after a meeting of several thousand students in the Great Hall in Earslfort Terrace. The students voiced their support of the occupation but called for it to end.

Arising out of the occupation and subsequent mass meeting, UCD students voted on three proposals, (a) that the Governing Body be reformed so as to delegate effective power to joint committees of staff and of students democratically elected; (b) that such a joint staff-student committee be set up to make all decisions pertinent to the move to Belfield; and that no decision should be made on the move without adequate consultation with the whole body of staff and students, whose directions they should obey; (c) that no student should be victimized for the occupation.

The motions were passed at a mass meeting held by over 5,000 students in the Great Hall on March 5th 1969. It also decided to boycott normal lectures from 9am the next morning, and to replace them with a “marathon seminar on the topic of a ‘free university’ ”.[20] A meeting of 250 members of staff registered their “general goodwill”towards the students.

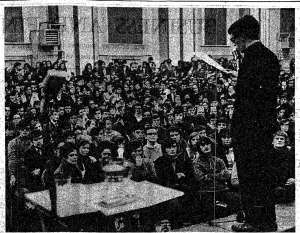

Student Meeting (March 1969, Great Hall, Earslfort Terrace).

Out in Belfield, a mass meeting of several hundred students issued their support of the actions and resolutions of the ‘teach in’ in Earlsfort Terrace. The ‘teach-in’ comprised of two large meetings in the Great Hall during the morning and afternoon attended by over 2,000 students in each case. These took place simultaneously throughout the College with debates on the topics (a) the internal structure of the university: (b) the university in society and (c) the problems of society.

Following these events, meetings were held between representatives of the student body and the Academic Staff Association (ASA) to help further proposals for the restructuring of the college.[21][22]Soon after, authorities gave in to student demands and announced that UCD students were to have the first Students’ Union in the country.[23] Throughout the Easter break, students and staff held several meetings to progress their aim of a “free university”.[24]

In May, 250 students occupied the administration building “in protest at against certain proposals in the Academic Council’s committee of Inquiry report” which included recommendations that students should be asked to sign a declaration of obedience annually. The student protest began with a public meeting at lunch hour organized by the SRC. Students then invaded three offices of the administration wing “using a mop as a battering ram to smash two doors” and immediately elected a 10-man action committee.[25] The occupation prompted the college to set up a committee to take disciplinary action against students involved. The SRC and SDA released statements declaring that they would ignore this new body.[26] In the end, nine students were summoned to appear before the committee where they were each given a formal warning that if they partook in similar behaviour again they would expose themselves to “permanent expulsion from the college”. [27]

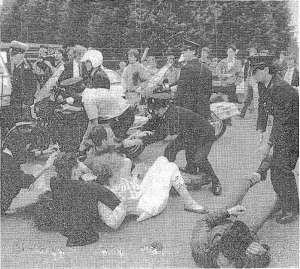

The Arts block was finally opened in September 1970, and soon become the home of 5,000 Arts students.[28] Scuffles broke out during the ceremony between Maoist protesters and Gardai.[29]

Gardai restrain two Maoist protesters during Arts Block opening protests

The full history of the student radicalism in UCD in the late 1960s is yet to be written. Let this be a start.

—

[1] University College Dublin (UCD), UCD 150 Year Celebration. Available: http://www.ucd.ie/150/sport.htm [Accessed: 5 February 2009]

[2] Donal McCartney, UCD: A National Idea, The History of University College, Dublin (Dublin, 1999), 345.

[3] ibid

[4]Irish Times Reporter, “Students Again On The Hunt For “Digs”, The Irish Times, September 11, 1963.

[5]A Special Correspondent, “Belfield: The Stimulating Prospect”, The Irish Times, September 23, 1964.

[6]President Dr. Jeremiah Hogan, “Progress At Belfield Outlined By Hogan”, The Irish Times, January 18, 1965.

[7]U.C.D. Correspondent, “Students Will Fight Fee Increase”, The Irish Times, December 24, 1966.

[8]UCD Correspondent, “In The Universities”, The Irish Times, May 31, 1967.

[9]Irish Times Reporter, “Students and O’Malley have talks”, The Irish Times, February 16, 1968.

[10]Irish Times Reporter, “Threat of Sit In at Belfield”, The Irish Times, October 30, 1968.

[11]Irish Times Reporter, “New Arts Building At Belfield”, The Irish Times, October 17, 1968.

[12]Education Correspondent, “U.C.D. “Sit-In” Was Good-Humored”, The Irish Times, November 9, 1968

[13]Anon, “Students take over hall at U.C.D”, The Irish Independent, November 9, 1968.

[14]Irish Times Reporter, “U.C.D. Students On 30-Hour Sit-In”, The Irish Times, November 30, 1968.

[15]Anon, “Students stage protest at U.C.D. council”, The Irish Times, December 13, 1968.

[16]Anon, “U.C.D. Notes”, The Irish Times, February 5, 1969.

[17]Irish Times Reporter, “Students Barricade U.C.D. Rooms”, The Irish Times, February 27, 1969.

[18]ibid

[19]Irish Independent Reporter, “60 students ‘barricade in’ at U.C.D.”, The Irish Independent, February 27, 1969.

[20]Anon, “Many staff join U.C.D. students in protest”, The Irish Times, March 7, 1969.

[21]Irish Times Reporter, “U.C.D. staff to meet students”, The Irish Times, March 14, 1969.

[22]Anon, “U.C.D. staff in favour of college reforms”, The Irish Times, March 20, 1969.

[23]Irish Times Reporter, “More powers for students at U.C.D.”, The Irish Times, March 20, 1969.

[24]Irish Times Reporter, “Hopeful start to U.C.D. discussions”, The Irish Times, April 18, 1969.

[25]Anon, “Campaign of protest in U.C.D.”, The Irish Times, May 20, 1969.

[26]Anon, “Student to ignore new committee”, The Irish Times, May 24, 1969.

[27]Anon, “U.C.D. council accepts finding on students”, The Irish Times, June 27, 1969.

[28]Michael Henry, “President opens U.C.D. Arts Block”, The Irish Times, September 30, 1970.

[29]Anon, “Protesters tangle with gardai”, The Irish Independent, September 30, 1970.